The unknown stories of an LZ student

A class of 2017 senior’s little known story of his sister with special needs.

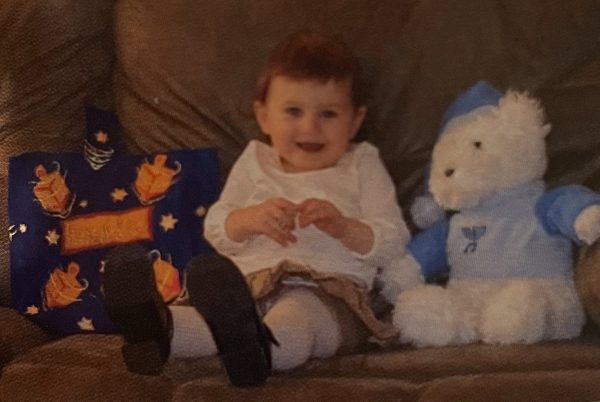

Photo by photo used with permission of Ryan Andrasco

Ryan Andrasco, senior, and his sister Kiley, posing for a picture. Kiley has a rare disease called Alternating Hemiplegia of Childhood (AHC).

The city of Lake Zurich has a population of about 20,000. Every year, students and families come and go, and every year someone meets a new person and makes a new friend. Every family has their highs and lows, but some families have to deal with something that most people can’t even imagine.

“My sister’s one of the lucky ones, I guess. She can walk most of the time. She can talk, with some impediments,” Ryan Andrasco, senior, said. “She’s 15 years old, but when you look at her, you’d think she’s still in middle school.”

Andrasco’s sister, Kiley, has a disorder known as Alternating Hemiplegia of Childhood (AHC), caused by a mutation of the ATP1A3 gene, according to ACHKids.org.

“About half the kids develop seizures at some point in their life,” Andrasco, said. “They’re all developmentally delayed. Some of them can walk, but their stride is awkward. Some can’t walk at all. Some of the kids can talk really well, some of them can’t talk at all.”

The disease is fairly new, discovered in the last 20 years, previously believed to be a part of the Autism Spectrum, due to similar symptoms. The symptom that sets it apart is paralysis, ranging from stiff limbs to not being to talk, according to Andrasco.

“[Kylie’s episodes] can occur multiple times a week. Some can last for a couple hours, and she’ll be fine after that,” Andrasco said. “Sometimes they can be on and off for three straight days.”

Along with the episodes of paralysis, kids with AHC suffer from emotional outbursts.

“They have a lot of behavioral issues, most of which stems from the inability to get their feelings across,” Andrasco said. “If there’s no one around, my sister will hit things in her area. She might just start banging on the wall or the door or knock something off her dresser, just trying to get attention to show that she needs something.”

In between the outbursts and episodes, Andrasco and his family have developed ways to communicate with Kiley when it becomes difficult.

“During an episode, she gets kind of stuck. We’ll come over and bring her over to a couch, sit her down, let her relax, if she calms down, it usually helps her get through some things,” Andrasco said. “If it gets to the point where she gets mad at someone and she gets aggressive, we have to give her space. Sometimes it’s worked where I pulled her aside and ask her to tell me about what’s happening.”

Although the Andrasco family has learned how to work through the episodes at home, going to school can be too much for Kiley.

“She goes to a school in Mt. Prospect that specializes dealing with kids who have emotional issues. While [Lake Zurich] has students with special needs, those students don’t have the behavioral issues,” Andrasco said. “She used to go to Middle School North, but she needed to be more secluded. Sometimes seeing all the people in the hallways was a sensory overload, which caused a lot of frustration.”

Because the disorder is so new, Andrasco and his family have been holding a walkathon for 11 years, trying to raise money for research. The oldest known person with the disease is in their 20s, according to Andrasco, which means no one knows what the future holds.

“Kiley wants a setup for the next day. She wants a list of what needs to be done, she wants her clothes all laid out so she doesn’t have to deal with that in the morning. The school works with them on that,” Andrasco said. “She’s made a lot of progress working with doctors over the years, but there’s obviously still a long way to go.”

Growing up with Kiley has made Andrasco more understanding.

“ A lot of my peers are quick to judge those struggling, or even make jokes about disabled kids,” Andrasco said. “I know what the kids are like, I know many of them through Kylie and I’m more sensitive to those comments and jokes.”

Andrasco understands that not everyone understand his situation, but he’s still grateful for the experience.

“Obviously every household has their own positives and negatives, but I would say that most people don’t have the scenario as mine,” Andrasco said. “Friends are usually shocked and don’t understand if I explain to them how my 15 year old sister has tantrums. But I have learned a lot from her, my family has, and I think we are all better people because of it.”

This is Danna's (pronounced Donna, not Dana) third year on staff and fourth year involved in the journalism program. She's on the Varsity Tennis team...